The spirit may be willing, but the flesh is indeed weak. I sold my Panasonic S1 after a year. Egads, you shriek, you seemed so excited, so fulfilled, what happened?!? Well, in the end, gravity won. Gravity always wins. I stand by the general thesis I put forward in my S1 review, namely that a little discomfort should not dissuade one from carrying the camera one wants to carry. But when the shiny newness comes off, a kilo and a half of camera on the shoulder does have a way of encouraging the consideration of options. I would have persevered if there were no other way, but what if I could have that beautiful EVF for half the weight? Yes, please.

Lose Weight Now with Fuji!

When I got the S1, there was nothing else even close to it in price that offered a 5 megadot EVF. But right around the time I was shopping for a used S1, Fuji introduced the X-H2. Back then it went for more than twice what I paid for the S1, but praise depreciation, not anymore. It’s not the screaming deal that the S1 presented a year ago, but it’s more palatable than when it was only available new at retail. Plus, once I sold all my L mount stuff, I actually got back more than I spent on the X-H2 and the lens I wanted, so it’s like I made money by buying another camera! My justification-fu is strong.

Why jump to Fuji? If you want to downsize while keeping a 5 megadot EVF, you really only have two options. There’s the OMDS OM-1, but while I know and love Olympus cameras, I wanted to keep the sensor a bit bigger than Micro Fourth Thirds. That means APS-C, and if you’re a gear-head, that means Fuji. Like its Fuji APS-C X-series brethren, and unlike anything from the competition, the X-H2 is an unapologetically serious camera. Outside of MFT, the other camera makers have prostrated themselves before the unholy alter of the “full frame.” The big three, for example, all offer APS-C versions of their mirrorless mount cameras, but it’s obvious that they exist only to lure in normies thinking of improving on their phones. They are not positioned as serious alternatives to the full frame bodies; they aren’t aimed at enthusiast photographers who might just want something smaller and lighter. To call the APS-C-specific mirrorless lens lineups from Canon and Nikon perfunctory would be charitable. Sony is better only because the E mount actually started as APS-C-only, back when full-frame mirrorless was a dream nobody was having yet, so for a while had Sony’s full attention, plus a bunch of third-party development. All of the recent APS-C bodies from the big three seem meekly committed to not cannibalizing sales of more expensive (and almost certainly higher margin) full frame options.

It takes a lot of glass to cover a full-frame sensor. Sure, it’d be more apples-to-apples if I had a 50mm f/2.8 on the S1, but that lens doesn’t exist.

Indeed, Fuji goes its own way. The X-T cameras have a control layout that flies in the face of the multi-function dials that have long been standard on digital bodies. The X-Pro cameras go a step further with a hybrid optical/electronic viewfinder that’s wholly unlike anything from other makers. Normcore dad that I am, went with an X-H camera: vanilla design with a PASM dial (cleverly, actually a PSAM dial), a pair of multi-function wheels, a brace of programable buttons. But it’s still unlike anything from the big three: a top-spec EVF in a relatively affordable, relatively compact body, with a full menu of lenses designed to take advantage of the smaller sensor — in some cases, barely bigger than roughly equivalent MFT glass.

Fuji also has a fun fandom around it. Consider if you will Fujilove “magazine,” an electronic publication that charges a princely ten bucks a month for access. In the interests of journalism I ponied up to see what it was all about — and I liked it! The featured photography is sometimes quite good, much better than random web stuff. Ditto the writing. And your ten spot also lets you download all the back issues, so It’s actually a pretty good deal.

A (Smaller) Room with a View

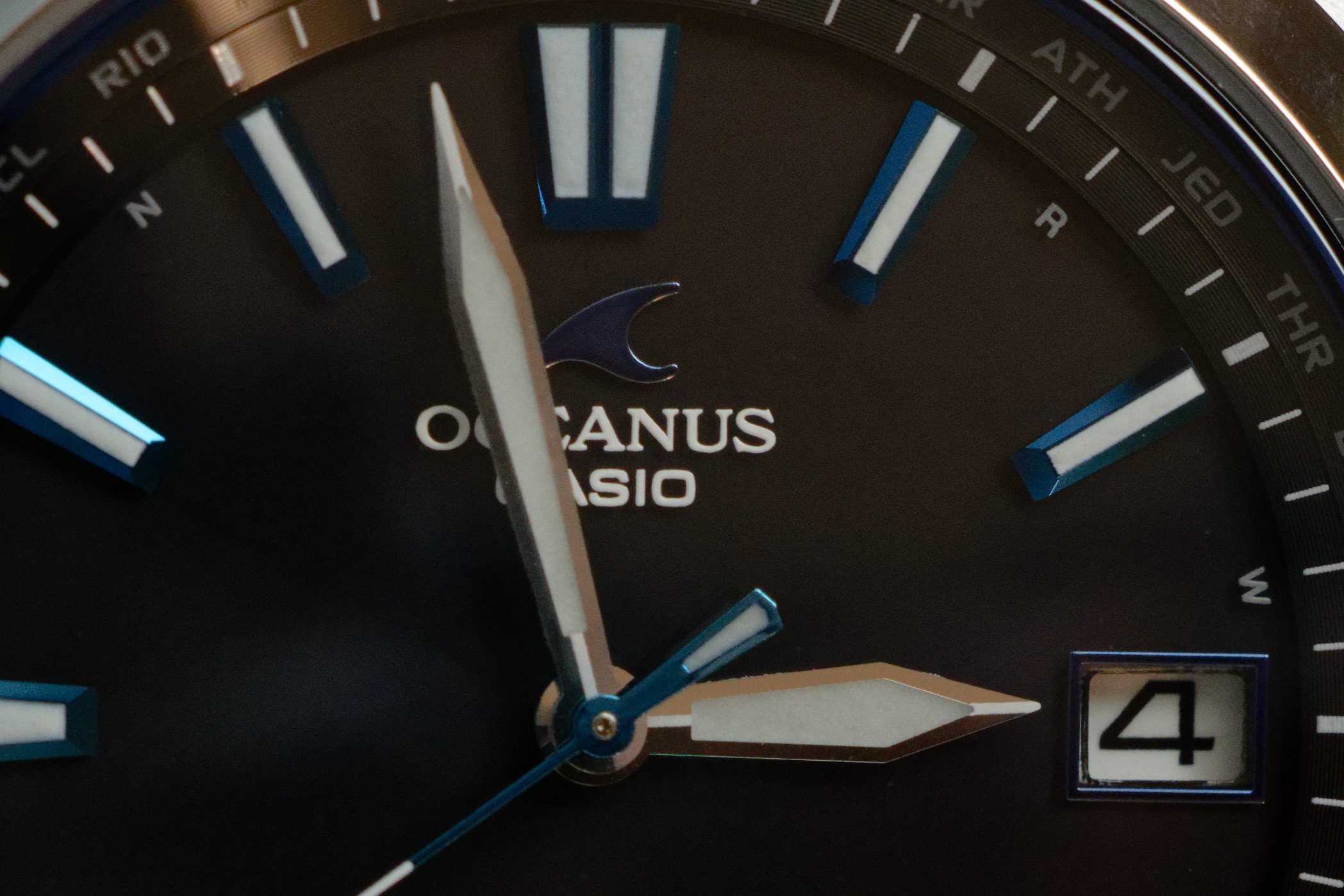

The X-H2 has been extensively reviewed so I’m not going to rewrite the wheel. Instead I’ll focus on my personal obsession, the viewfinder, which gets short shrift from reviewers and is almost never considered in the context of the wider market.

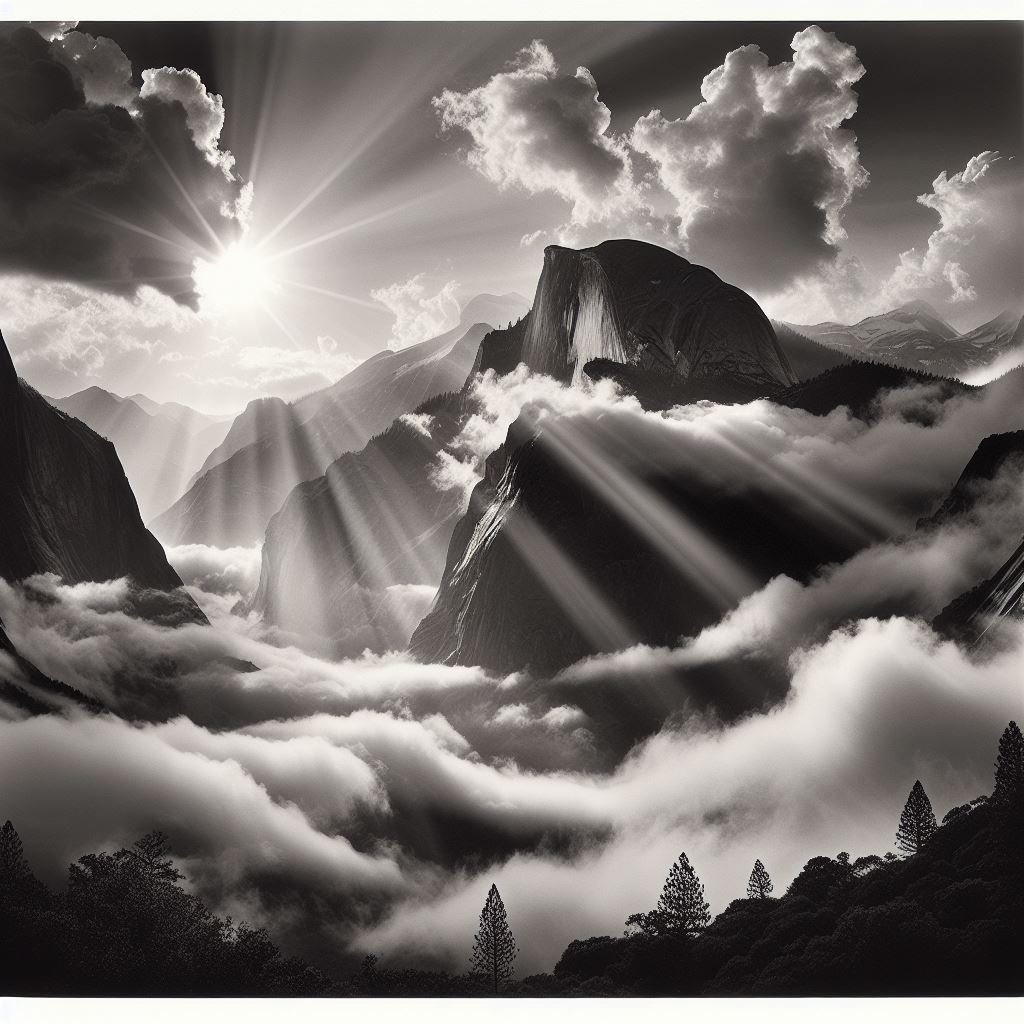

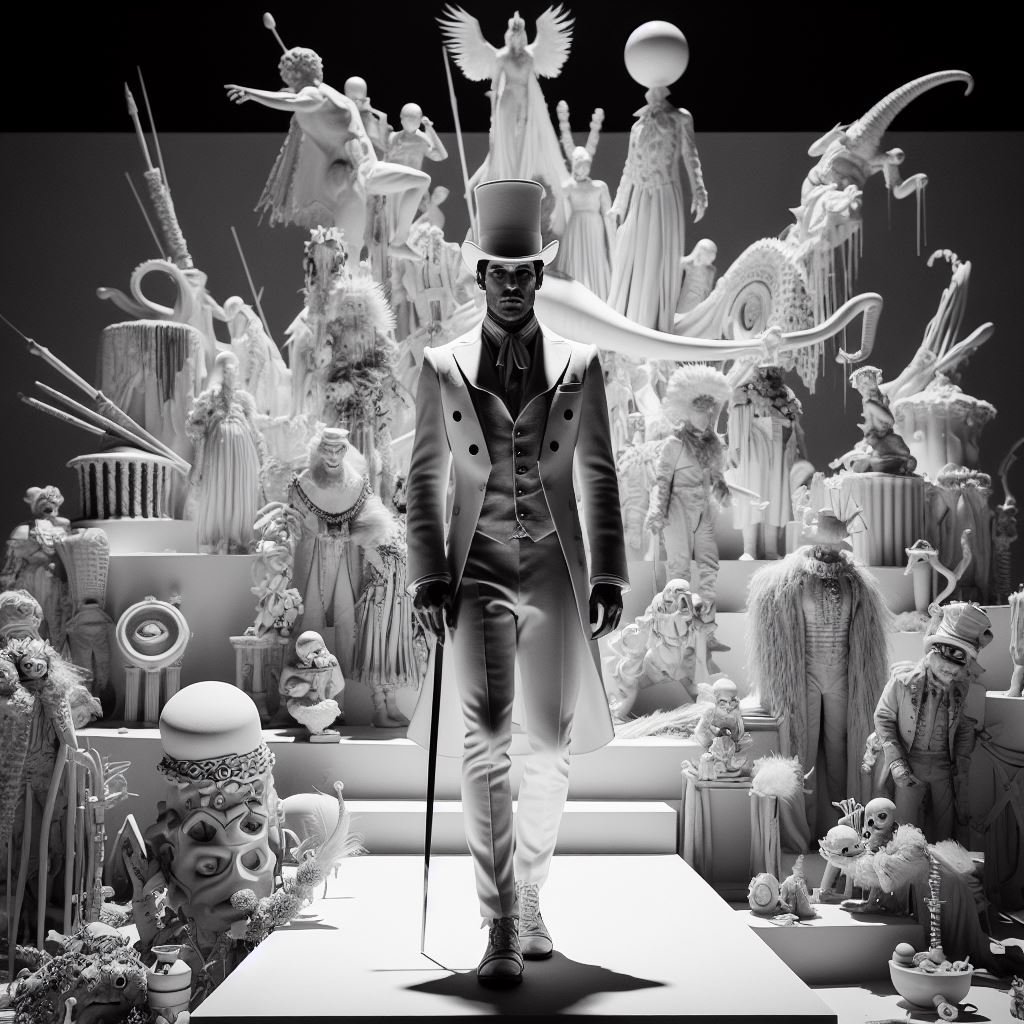

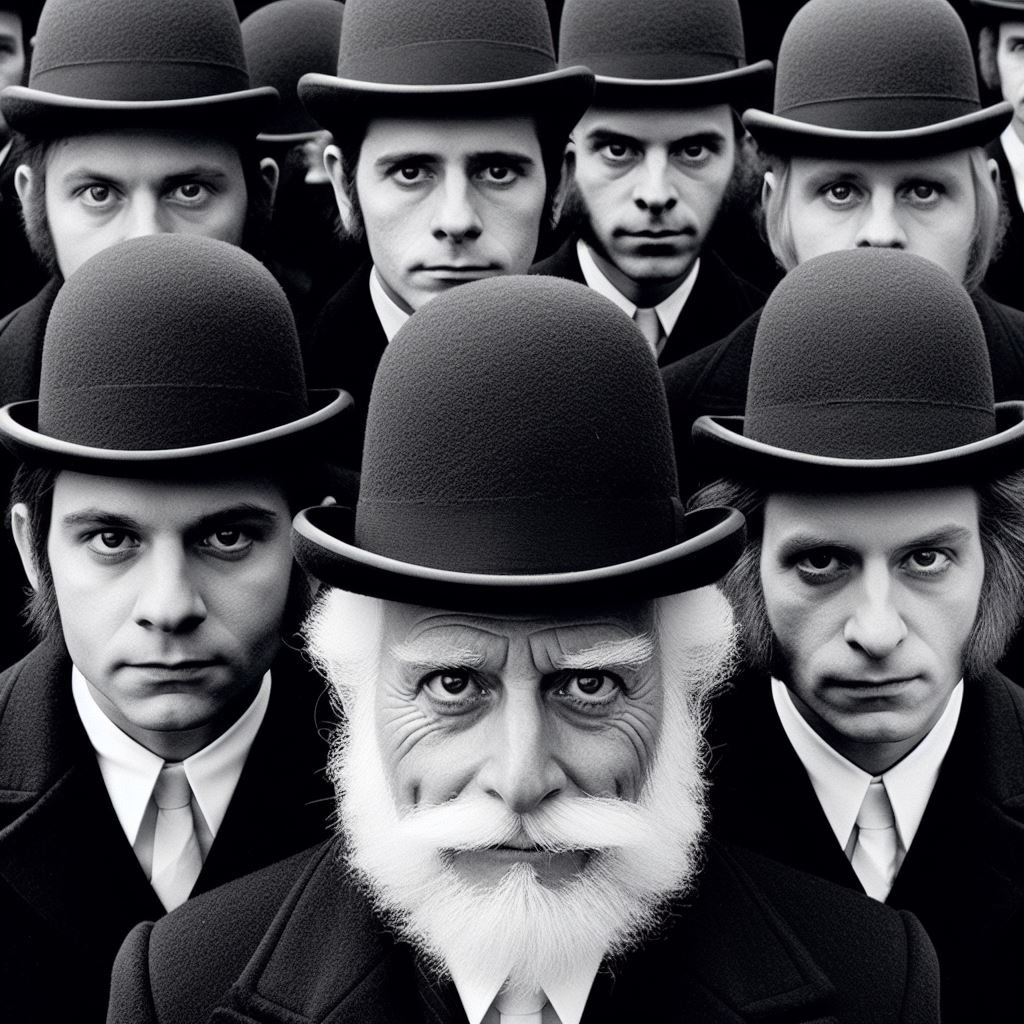

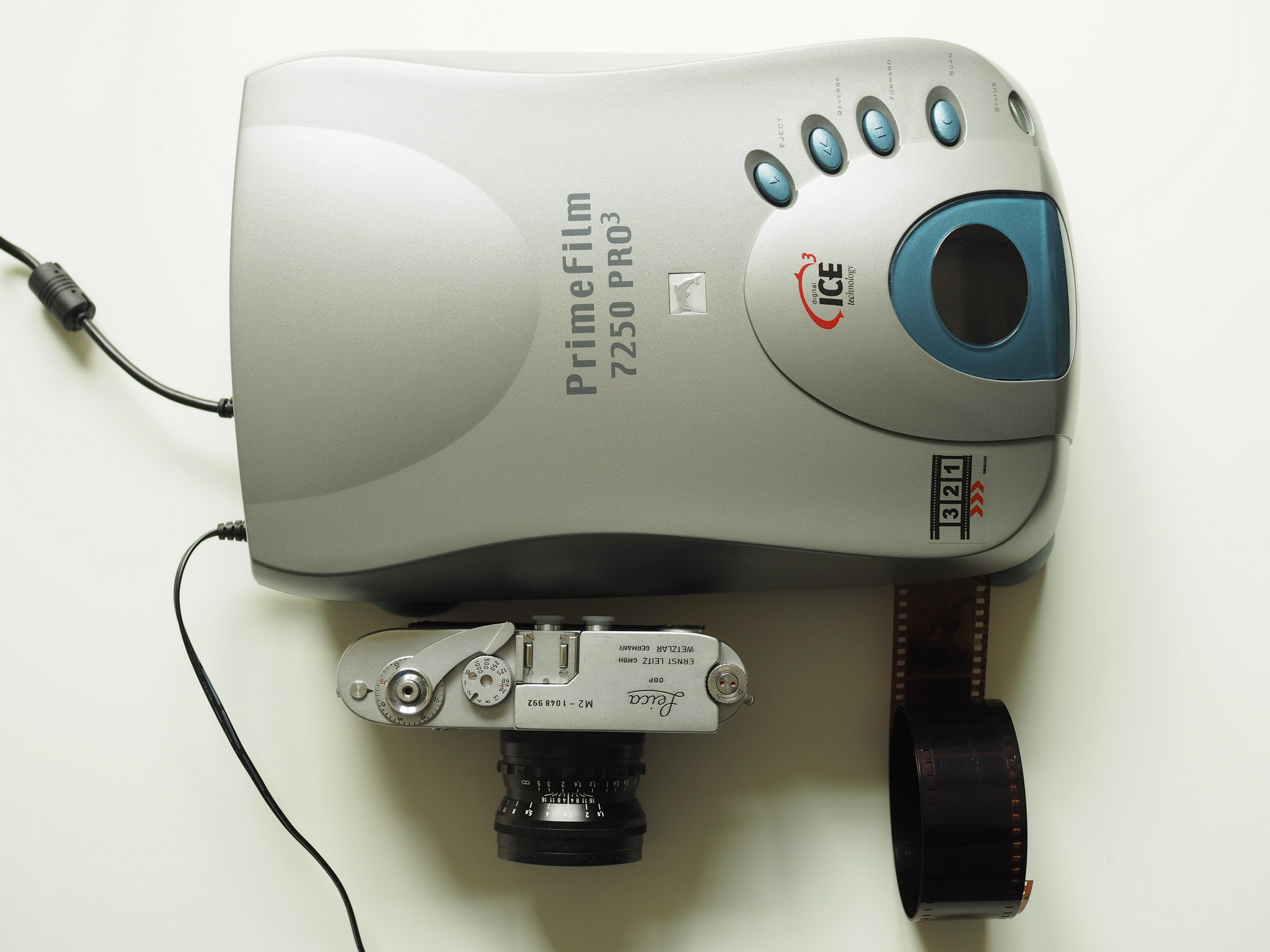

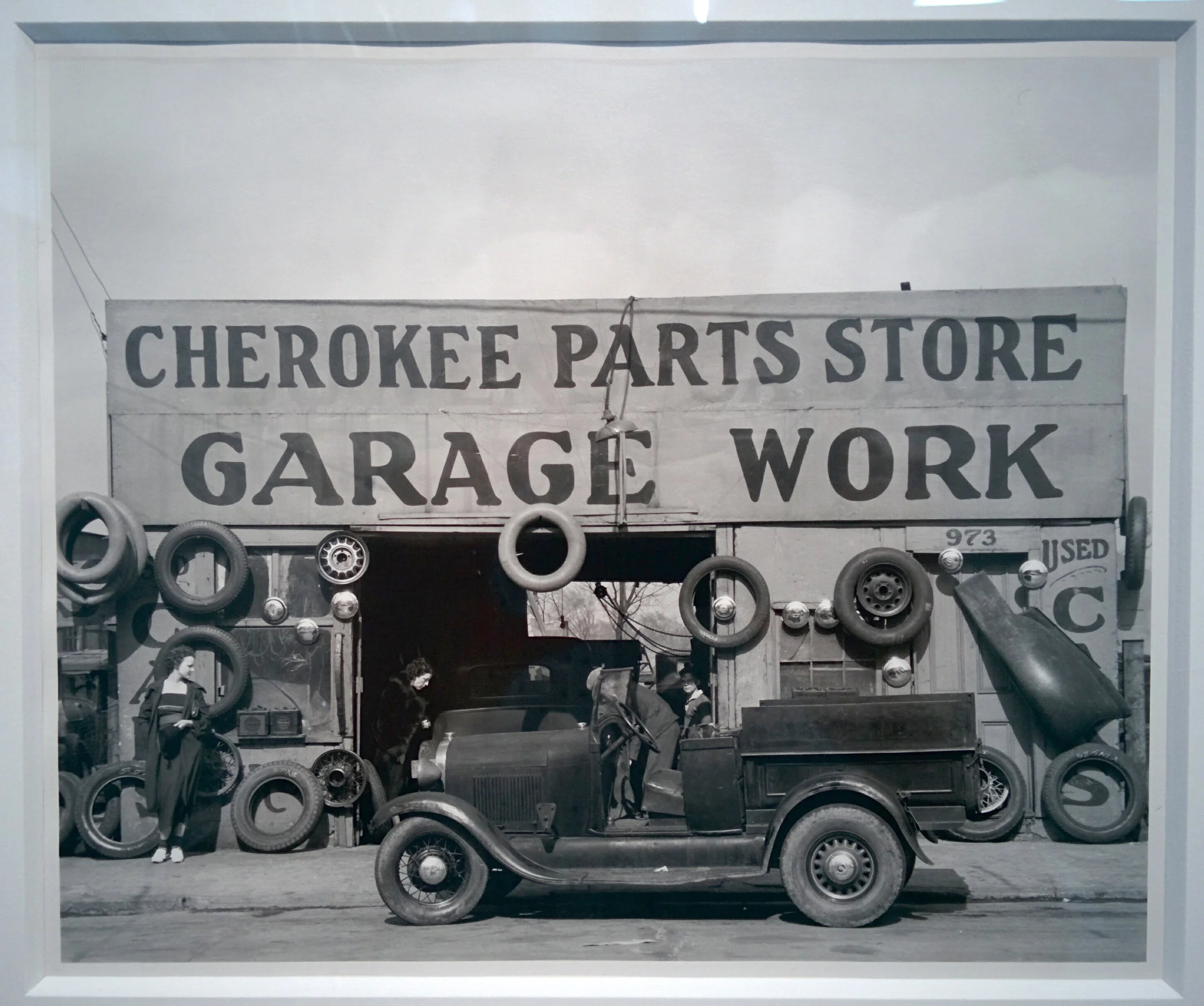

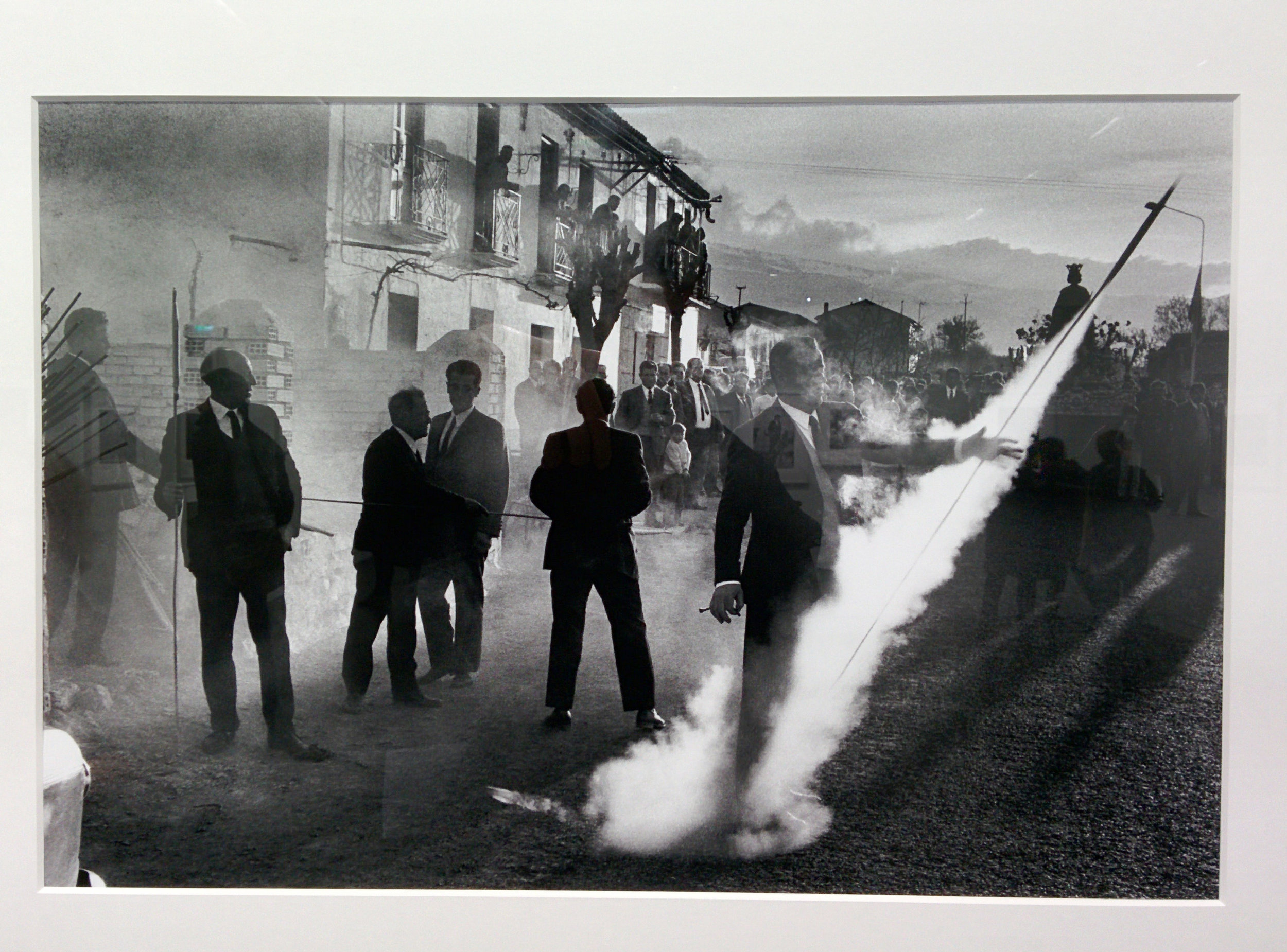

I don’t have any more relevant illustrations, so from here on I’ll break up the text with photos taken while looking through the X-H2’s viewfinder.

The best EVFs on an APS-C body from any of the big three still use the 2.4 megadot panels that were state of the art eight years ago. But oh ho, Fuji’s APS-C X-H2 has a 5.76 megadot panel behind beefy .80 x mag finder optics, in all likelihood better than the 3.69 megadot panel in the $8,000 full-frame Nikon Z8. Regular readers will know how I fetishize EVF performance, and won’t be surprised that the X-H2 caught my eye (so to speak) as soon as I got tired of lugging the S1.

So how do the viewfinders of the Panasonic S1 and the Fuji X-H2 compare? The short answer: the Fuji’s is a bit better. While the panel resolutions are equivalent, one thing you quickly figure out if you embark on the tortured road of EVF connoisseurship is that the panel is only part of a system with a lot of inputs, hardly any of which get discussed in most reviews (rarely for the model under review, and even less in comparison to other models). For example, a dirty secret is that the physical panel resolution spec is not always indicative of the actual resolution of the preview image. In side by-side comparison, it became clear to me that even when both cameras were optimally configured for detail, the Fuji was pushing a little more information to the panel than the Panasonic. The difference was subtle, most visible in something like text, but it was there.

Both cameras also cut resolution dramatically when engaging the higher frame rate options on the EVFs — the Fuji implies this will happen by the way the options are named, but the Panasonic menu options treat frame rate like a choice without consequences.

Apart from detail levels, I found little to distinguish the viewfinder image quality. The slight magnification advantage of the Fuji (.80 vs .78 for the Panasonic) was hard for me to detect even when moving my eye from one finder to the other, much less in isolation. The accepted gospel is that bigger is better with viewfinders, but I feel that both EVFs are already pushing right up against practical limits of how big a viewfinder can be without interfering with composition. When I look at the center of the VF, I want to be more or less aware of what’s happening towards the edges so I can compose without roving my eye around the frame. I can still do that with the Fuji, but only just. At any higher magnification, I would probably resort to using a display mode that leaves a border around the image.

Magnification is largely a function of optics (I think all of these 5 megadot panels are the same size, if not actually the same part) and I wondered if I’d see differences there. With the S1’s massive size, I was worried that Panasonic had managed better corrected optics than the Fuji’s flattened “prism hump” would allow. But I could not really see a difference. Both are sharp right to the edge of the image, and don’t force the user to refocus their eye to see into the corners. Both offer good enough eye relief (I don’t wear glasses — yet). In both I detected an almost subliminal barrel distortion but it only showed up if I looked for it. It could have been in the lens, or some miscorrection the camera was doing to the lens image, or the optics. It was nothing I’d worry about.

Nobody quotes brightness or contrast specs for EVFs, but I did not notice a difference. The S1 has a really nice eye cup to keep extraneous light out of the way, but I have not had many problems with the Fuji in the few bright light situations I’ve shot it (it being winter in France as I write this). Contrast ratios also seem similar, though I don’t have a way to empirically test it. Both are OLED panels, which by definition offer nice deep blacks (and again, they might be the same panel — maybe the one Sony announced in 2018, but I’m just guessing).

Although the S1 is my main point of reference, I did have a chance to compare the X-H2 EVF side-by-side with a Sony A7 IV. As of this writing it’s the latest offering in Sony’s mainstream full-frame lineup, and although it’s a bit long in the tooth, it still runs about $600 more than the X-H2 at B&H. But like most of the current crop of high-end cameras, it has a 3.68 megadot EVF. This is a smaller number than 5.76, but since you have to think of resolution as width and height multiplied together, the linear specs encourage an overestimation of the difference. And maybe this is why so much of the market is content to sit at 3.68 megadots. But looking through the A7 IV’s EVF, I was surprised to see significantly less detail in the image. I have to believe that, just as the S1 doesn’t seem to take full advantage of its high-res panel, the Sony is also starving its EVF display. Processing limitations, power consumption considerations? I don’t know. The Sony also seemed to cut corners on EVF optics: I had to refocus my eye a bit to get sharp in the corners, and there was some subtle pincushion distortion.

Two niggles have emerged during my use of the X-H2’s EVF so far. First, I almost immediately noticed that with AF-C engaged it flickers like crazy when used under the lighting in my living room, which is where I take a disproportionate number of photos of my beautiful family. As it happens, we just redid the whole room and I picked out most of the bulbs, and because I care I tried to stick to Philips as much as possible. So these aren’t weird off-brand bulbs that you might buy in a convenience store. Plus, none of my other cameras take exception with them. I tried messing with the anti-flicker settings even though I think those only apply to video capture, but in any case it didn’t help.

Second, a few times I’ve pulled the camera quickly to my eye and had to wait for the EVF to kick on. When it happened I imagined that it was my whip-quick Cartier-Bresson-like street photography style that was the cause, but in fact when I consciously try to out-speed the eye sensor, I can’t — it switches from screen to EVF essentially instantly. Someone suggested to me that in bright light the eye sensor might have trouble, but I have not noticed a correlation between ambient light levels and this glitch. If you’re reading this and have ideas, feel free to share.

Who Cares?

If you’re read this far, you apparently have the same unhealthy obsession with viewfinders that I do. It may be worth stepping back to ask if any of this matters. EVF technology has long surpassed the essential needs of the photographer; all it really has to do is provide enough of a preview to allow for effective composition. A secondary benefit unique to digital capture is that the preview can help judge proper exposure; this was never even on the menu with optical finders, but we expect it in the world of EVFs.

Any mid-range or better camera of the last several years meets these basic criteria. So why get sweaty about this or that OLED panel? For me, it’s not just a question of aesthetic pleasure (though it is that). As a photographer, you already make a substantial sacrifice each time you put a camera in front of your face. You trade, however briefly, the experience of seeing now for the promise of seeing later. You make it possible to revisit a scene, for yourself and others, but at the price of not quite being there as it happens. No viewfinder, no matter how “good,” can change the fundamental economics of that transaction. But a nice EVF does give you a better view of what you’re missing, and that’s not nothing.